A Q&A with director Marnie Blok reveals the deeply personal journey behind “Beyond Silence,” a powerful exploration of trauma, generational divides, and the cost of speaking out.

When writer-director Marnie Blok took the stage after a screening of her Oscar-qualifying short film “Beyond Silence,” she didn’t shy away from the raw truth that fuelled her work. “I was raped myself,” she stated simply, “and so I think I had to focus on the subject. And I have a huge anger on the subject, and that’s a very real, good place to create from.”

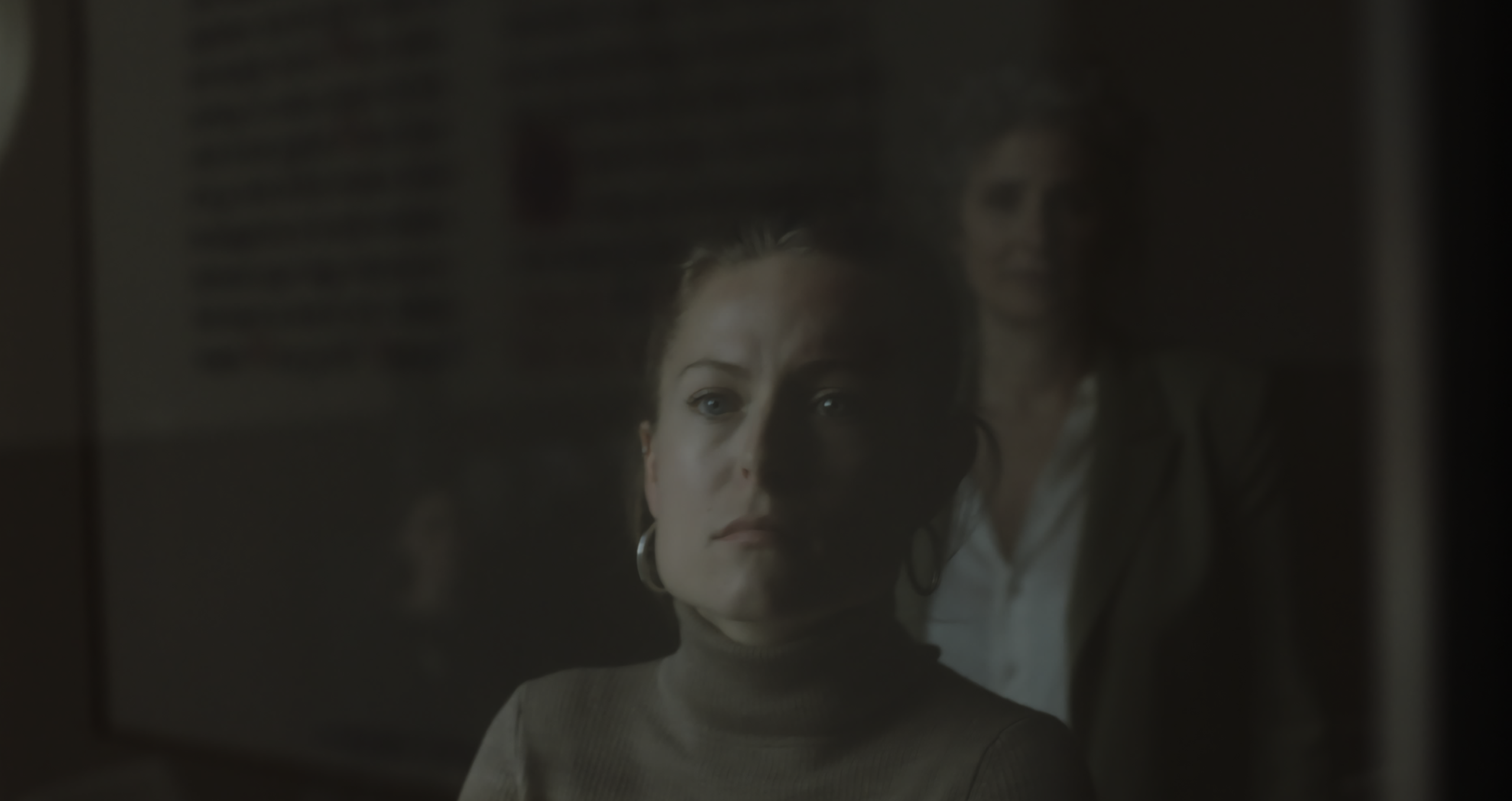

That anger, transformed into art, has resulted in one of the most talked-about contenders in this year’s Best Live Action Short category – a film that examines two women, two generations, and one shared trauma through the unique lens of a deaf protagonist.

The Personal Becomes Universal

Blok’s journey to this film began decades ago when, as a young actress, she wrote her first script about rape, centred on the theme “a happy life is the best revenge.” Though that script was never produced, the idea stayed with her. Years later, after conducting research in the wake of the #MeToo movement, she discovered a sobering statistic: despite a 60-70% increase in reports of sexual abuse and violence, actual charges pressed only went up by 1%.

“That made me realise how huge the group of people is that are silenced either by themselves or by others,” Blok explained. “I thought, I need to write something else now, which is about breaking the silence and also about the costs of breaking the silence.”

Two Generations, Two Responses

The decision to feature two generations in the film came from Blok’s observations of reactions to #MeToo, particularly from older women who dismissed the movement or advised against “becoming a victim.” While she understood this defensiveness – having herself downplayed her own assault for years – she recognised it as fundamentally flawed.

“If you are raped, you are a victim and there’s nothing weak about that. That’s a fact,” she emphasised. “And talking about it is especially nothing weak, it’s very strong.”

This generational divide is embodied in the film’s two lead characters, played by first-time actress Henrianna Jansen and veteran Dutch actress Tamar van ten Dop.

A Groundbreaking Casting Choice

Perhaps the most striking aspect of “Beyond Silence” is Blok’s decision to cast Jansen, a deaf actress, in her debut role. The choice was both practical and metaphorical – Blok wanted to explore the idea of not being heard through the literal experience of deafness.

“We do not have deaf actresses in Holland because they are not allowed to go to the theatre school, or at least that happened when Henrianna tried to get in,” Blok revealed, highlighting systemic barriers in the entertainment industry.

Working with an actress who had no formal training required an unconventional approach. Rather than traditional rehearsals, Blok took Jansen boxing. “I didn’t want to rehearse the text with her from the script,” she explained. “I knew if you start acting, you have this bird’s eye view, you are too conscious. So I felt she was very much in her head, so I thought, well, let’s go boxing.”

The strategy worked. By exhausting Jansen physically before running the monologue, Blok helped her connect to the character’s emotional core through her body rather than her intellect.

Kitchen Table Sessions and Shared Trauma

The preparation process involved countless “kitchen table sessions” where cast and crew shared their stories and built trust. Jansen drew parallels between her own difficult life experiences and the character’s trauma.

“For me, it’s been a hard life and it had a really big impact on my life and I lost my life in a way,” Jansen shared through her interpreter. “So the rape of Marnie and my feeling was also very emotional, so I could put the two emotions in the character of Eve.”

Van ten Dop, meanwhile, brought her own perspective as someone who came of age in a film industry very different from today’s. “When I started working in cinema, it was on film and not digital, and the world was very different. There was not a lot of solidarity between women, it was a man’s world,” she recalled. At 20, she was already playing mothers to 10-year-old children, navigating an industry where survival meant “manning up” and being tough.

“Now I see that this younger generation of women, they have a larger solidarity, and they have a different view on this world,” van ten Dop observed. “The very young ones were far more open about their vulnerability and about what was not feeling safe, and they already had words for it.”

The Power of Close-Ups and Sound Design

Working with cinematographer Myrthe Mosterman, Blok created an intimate visual language focused on faces, eyes, and physical details. “I want to be with the characters. I think for me, authenticity in playing is really key,” she explained. “So I want to look in the eyes and be close to them.”

The sound design presented unique challenges. Blok initially wanted complete silence to represent Jansen’s perspective, but discovered that total absence of sound felt “horrible” and didn’t work cinematically. The solution came through experimentation, with the sound engineer creating a distinctive auditory world that suggested Jansen’s experience without attempting to literally replicate it.

Made on a Shoestring, Crafted with Care

The entire film was shot in just 21 hours over three days, with a crew that worked continuous shifts without proper lunch breaks and minimal pay. Yet this constraint created its own energy. “If you know you have very short time and you want to do it together, you go,” Blok said simply.

The film’s powerful ending came together almost by accident. After the originally planned conclusion didn’t work, van ten Dop improvised – and Blok knew immediately she had her final moment. “That’s what you get when you have an actress like that,” she noted with evident appreciation.

The Gaslighting We Do to Ourselves

One of the film’s most crucial lines almost didn’t make it in. The character played by van ten Dop tells the younger woman, “You want equal rights and equal chances, then you also have to take equal responsibility.” Some questioned whether this victim-blaming perspective should be included.

“Then suddenly I knew we had to put it in because that was basically the most important sentence that she says, and it’s difficult for her to say,” Blok explained. The line represents the self-gaslighting that many survivors engage in, the internalised message that they somehow bear responsibility for their assault.

The Call for Accountability

Closing the Q&A, Blok emphasised that systemic change requires more than survivors speaking out. “If we want to change this ongoing problem, which has been there already for ages and ages, I think we need men, first of all, and I think there is a really decisive role to be played by bystanders.”

She acknowledged the difficulty bystanders face – perpetrators ask them to stay silent, while victims ask them to challenge the system. “But that’s really what we need,” she insisted.

“Beyond Silence” stands as both a deeply personal statement and a universal call to action. In just minutes of screen time, it captures the complexity of trauma, the weight of silence, and the courage required to speak – whether with voice or through sign language, whether after one year or thirty. It’s a film that refuses easy answers, instead offering something more valuable: recognition, rage, and the radical act of being heard.

“Beyond Silence” is qualified for Best Live Action Short at the 97th Academy Awards.

Editor in Chief of Ikon London Magazine, journalist, film producer and founder of The DAFTA Film Awards (The DAFTAs).